In the last chapter we learned about the so called Quick-turn. But how do we stop a sailboat if we reached a destination even by Quick-turn, by beating or by sailing any other course.

On the figures in this chapter we see a buoy that is the destination we want to stop at. The wind is blowing from the top of the image and the flag on the buoy points to the bottom. So on which course can we stop a boat at the buoy? On close-hauled, beam reach and broad reach a boat does not stop. Equally when sailing downwind the boat sails past by without stopping. The only course a boat stops is … ? Right, in irons. We have to shoot up and head towards the wind to get there. The wind slows down the boat and eventually stops it. But how do we do this?

How do we get into a position from where we can sail up, heading towards the wind and stop exactly there where we want to. As we can see on the figures the destination (in our case the buoy) has to be windward of the boat to shoot up to it. Therefore the boat has to be … ? Right, leeward of the buoy.

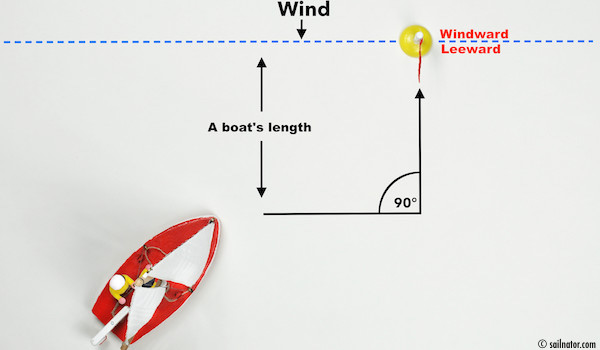

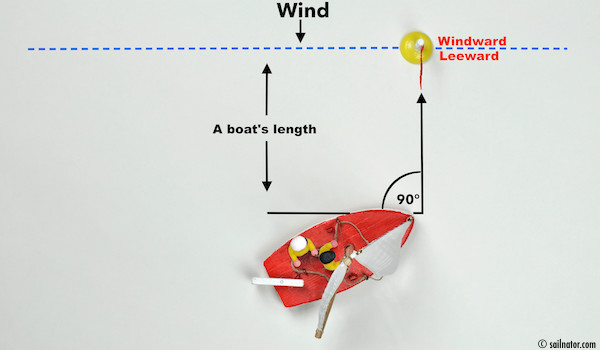

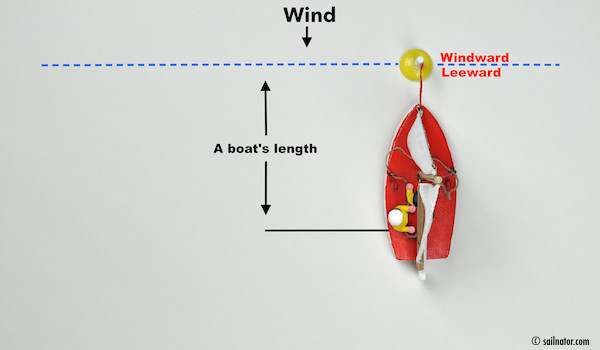

Figure 64: Approach from leeward to a line of a boat’s length distance parallel to the windward-leeward line.

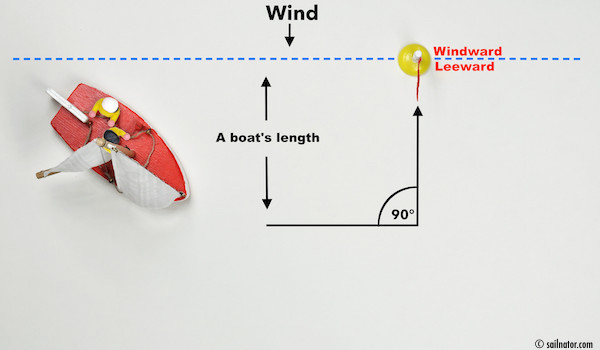

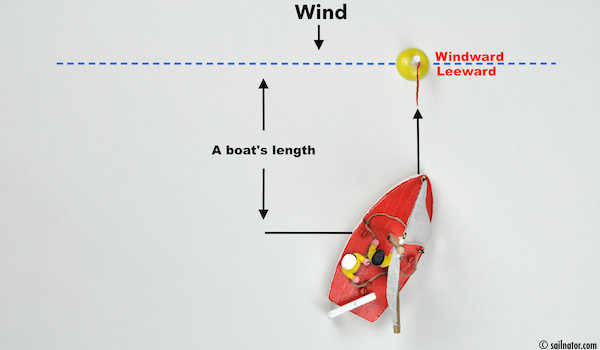

Figure 65: Approach from windward to a line of a boat’s length distance parallel to the windward-leeward line.

As long as the boat is windward the buoy we have to … ? Right, bear away to head up to the wind later. (Figure 65) If we are leeward the buoy we have to approach either on close-hauled, by beating or on beam reach. (Figure 64) Anyway, there are areas windward and leeward of the buoy and I call the imaginary dividing line between them the windward-leeward line.

To shoot up to the wind we have to be leeward of this line. But how far? Every boat needs a certain distance for stopping. Some stop immediately and others go on running very far. Furthermore we have to take the wind strength into account, as it also influences the distance. When do we stop faster? In strong winds, when we sail fast, or in weak winds … ? We sail faster in strong winds, but the power of the wind also stops the boat quicker. And if there is wind we usually have waves too, coming directly towards us, when we shoot up head to wind. They slow us down as well.

A rule as thumb is that there should be a distance of one and a half or one boat’s length between boat and goal. But you have to find out for yourselves. As I have explained before, it depends on the boat and on the conditions. You develop a feeling for the appropriate distance quite soon. But from where is the distance measured and in which angle to the buoy?

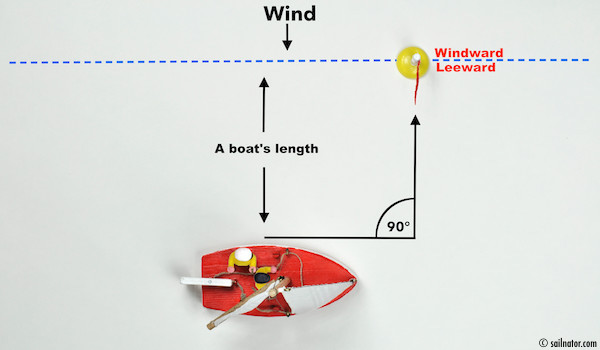

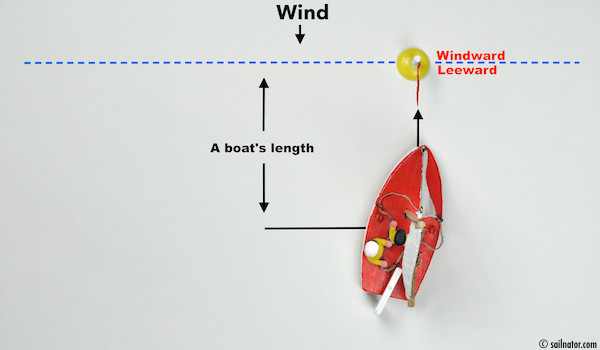

Figure 66: Command: “Ready to shoot up?” Answer: “Ready!”

To shoot up head to wind we approach the buoy, leaving a distance of one and a half or one boat’s length parallel to the windward-leeward line. (Figure 66) By doing so we find ourselves in an angle of 90 degree to the true wind. Why to the true wind … ? When we sail up head to wind we stop the boat. The wind of motion is not there anymore and we therefore use the true wind for the manoeuvre. Which course will it be, when we sail in an angle of 90 degree to the true wind? Probably close reach. That is the area between close-hauled and beam reach. It depends on how fast we are sailing.

But how do we measure the true wind? Our buoy on the figures carries a little flag. The wind blows it leewards. That is exactly the direction from where we have to shoot up head to wind. But we do not have this tool available to us all the time.

As a rough guidance we can use the waves that the wind drives in front it. The wave that is just by the buoy makes the windward-leeward line. We sail parallel in relation to this line in a distance of about a boat’s length. And simply by doing this we have the angle of 90 degrees to shoot up head to wind. Most certainly we do not use the initial wave all the time. That one heads towards us slowly and the distance gets shorter. But we always watch the wave that is just under the buoy.

This online sailing course has also been published as ebook and paperback. For more information click here!

This online sailing course has also been published as ebook and paperback. For more information click here!

You can download the Ebook for example at:

iTunes UK & iTunes US | iBooks for iPad and Mac

Amazon.com & Amazon.co.uk | Kindle-Edition

Google Play | for Android

The paperback is available for example at:

Amazon.com | Amazon.co.uk

So, as we approach the buoy leeward in a distance of about one boat’s length parallel to the wave that is cutting the buoy. When do we have to steer directly towards the buoy? We have to calculate that a boat needs a certain time to take an angle of 90 degrees. So we should start the manoeuvre a little bit before we reach the angle. For many dinghies this is about a boat’s length.

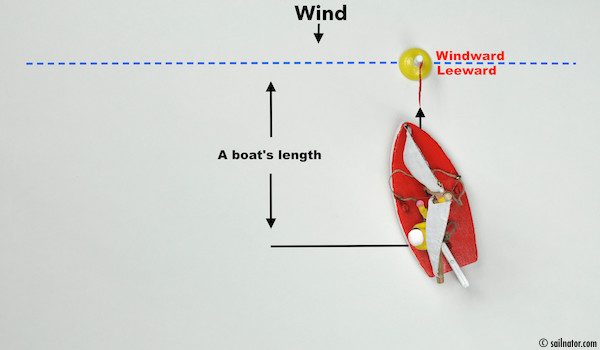

What do we have to do when we want to get into the wind … ? Right, we have to head up. What do we have to do with the tiller … ? Right, we push it away and steer in the direction of the buoy. (Figure 67) To really stop the boat the sails do not have to fill with wind anymore. So we release the sheets now and the sails go to the direction the wind blows to.

Figure 67: Command: „Release sheets!”

Figure 68: Head up and steering to the direction of the buoy.

The boat is correctly up head to wind when the boom is exactly in the middle of the boat. If not, we follow the boom with the tiller. For example the boom is still starboard, the tiller points starboard as well (Figure 69) and follows the boom till it is located in the middle. If the boom skips to port side the tiller points to portside too. (Figure 70) So if the tiller always follows the boom in its movements it will level off in the middle. And the boat stops. (Figure 71)

Figure 69: Thereby the tiller always points to the boom.

Figure 70: If the bow goes to port side, the tiller points to the boom that is skipping to port side too …

Figure 71: … and follows it till the boom is located in the middle and the boat stops.

The boat hopefully stops at the point we intended. If not (because for example the distance from where we started to shoot up was too long or we misjudged the wind force) then that is no problem.

We pull the jib away from where our destination is, in order for it to fill with wind from the back. We position ourselves on the same side and point the tiller towards our intended destination. The wind will push the boat backwards and turn it. Then we start the manoeuvre again. But most often we cannot control where the boat heads to, because the waves throw us to one or the other side. Then we bear away, sail away for a while and tack. By sailing back we search for the right distance to the 90 degrees angle to the buoy and try to shoot up again. Only practice makes perfect.

Incidentally the manoeuvre can be influenced by how we drive the 90 degrees angle. A fast and fierce turn slows us down more than a wide bow, which reduces the boats’s speed less. But the distance without wind in the sails increases and the danger is that we get stuck too early.

Watch my stop motion video about to sail up head to wind →

As a command for shooting up head into wind you can say:

“Ready to shoot up?” “Ready!” “Release sheets!”

So what is important when sailing up head into wind … ? To do so we have to be leeward of the destination. We go for it with about a boat’s length distance parallel to the windward-leeward line. About a boat’s length distance in front of the destination we start to shoot up. The sheets have to be released so that the boom can swing and we steer in the direction of the goal. While doing so the tiller points to the boom all the time, which levels off to the middle of the boat by time. As mentioned already, only practice makes perfect.

Now we know about the points of sail, tacking, the Quick-turn and how to shoot up head to wind. With all this we are ready to rescue a person that went overboard. The manoeuvre is called: “Man overboard” and I will explain it to you in the next chapter.

← Last chapter | Next chapter →

All chapters: Technical Terms | The theory behind sailing |Close-hauled | Beam reach | Broad reach | Sailing downwind | Tacking | Beating | Quick-turn | Sailing up head to wind | Man overboard | Jibing | Heaving-to | Leaving the dock | Berthing | Rules of the road 1 | Rules of the road 2 | Rules of the road 3 | Reefing | Capsizing