In the last two chapters we talked about the Quick-turn and how to sail up head into the wind. That was the preparation for the following manoeuvre: Man overboard

Of course we hope that it never actually happens and we can do a lot to prevent somebody from falling overboard. But if it does happen, we should be prepared. Usually the water is cold and the chance to survive is much higher when rescued quickly. There are different procedures to rescue a man overboard but the one I will explain to you now, is the easiest for beginners.

When practicing it this way, students learn a lot about how to sail and they get a good feeling for the boat and the wind. When you are more experienced later on, you can try out other procedures to find out which is the best for you and of course also the fastest. That is a bigger challenge and will help you to become a good sailor. But in the beginning you would be confused by too many options. So learn the basics first thoroughly and become an expert later on.

I actually do not like to talk about “Man overboard” when explaining it or practicing it. It should only be called “Man overboard” in case of a real emergency. Everybody should know that a man (or a woman or a child) really has fallen overboard. While practicing I always call “Buoy overboard”, because instead of a person we throw a buoy into the sea and the students try to get it back on board. And everybody knows that it is only training.

But how does a basic “Buoy overboard” manoeuvre works? On the figures in this chapter I assume that we sail close-hauled when the buoy falls overboard. What happens next? Confusion is great, everybody acts chaotically, there is no clear line about what should be done. The boat sails away from the buoy and the crew loses sight of it. Fatal if it would have been a person.

When the waves are about 3 feet high, you cannot see the head of a swimmer after a distance of about 120 feet anymore. So it is very important to coordinate the whole procedure. That is the job of the helmsman and he does so by using commands. As I told you before commands are not the same in every country or even on every boat. You have to be sure before leaving the dock that you and your crew are on the same level through clear communication. Everybody on board should be able to understand the terms you use; even non-sailors who are for example guests on the boat. And that is one of the reasons why the first thing we do with a new crew is to practice “Man overboard”. Actually you cannot practice it often enough.

But to coordinate the manoeuvre the helmsman has to know that in our case the buoy has fallen overboard. The first one to recognise it yells: “Buoy overboard on … side!” That depends on which side of the boat (starboard or port side) the buoy has fallen into the water.

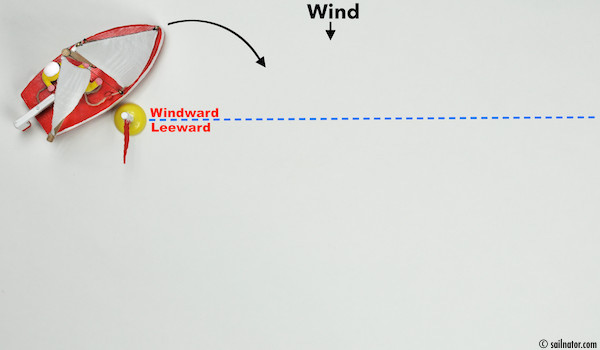

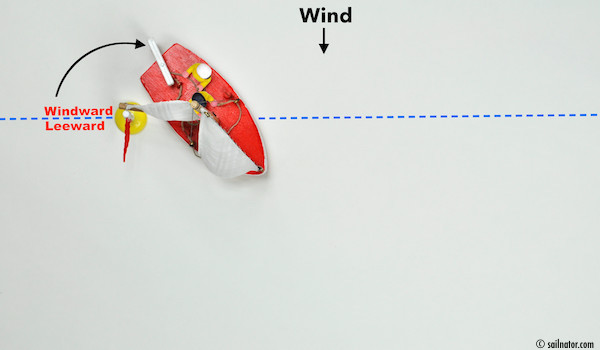

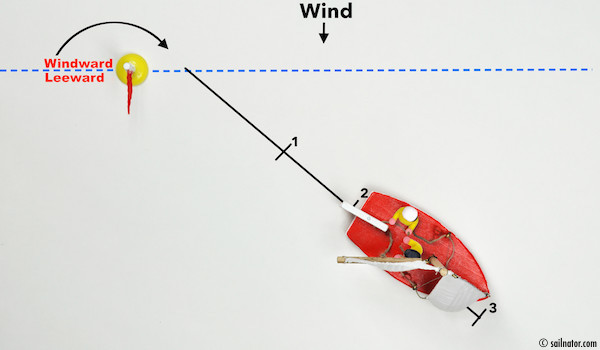

Figure 72: The buoy falls overboard. The crew member who realises first yells: “Buoy overboard on starboard!”

The buoy on figure 72 fell overboard on … ? Right, starboard. To signal his awareness of the situation the helmsman repeats the command loud enough for everybody to hear it: “Buoy overboard on starboard!” Next he chooses one member of the crew who has to keep an eye on the buoy. The helmsman commands: “Lookout so and so!” (Figure 73) It is definitely an advantage to know the names of the crewmembers. If not we point at somebody. The lookout has nothing else to do from now on but to keep the buoy in sight and to point at it with his arm. The helmsman now calls the next command: “Throw life ring!” and the crew starts to throw everything that helps to rescue a person into his direction. The captain has to show to the crew how the personal buoyancy that is on board works and where it is before leaving the dock.

Meanwhile time flies and we would have sailed quite a long distance if the helmsman would not have started a manoeuvre while calling the commands. To know what he should do we have to think about our plan and where we have to go for it.

Our plan is to get the buoy back on board. To do so we have to get to it. While sailing we might be able to grab a light buoy, but certainly not a heavy human being. So we have to stop the boat to bring a man (or a woman or a child) back on board. How do we stop a boat … ? Right, by shooting up head into wind! Where do we have to be to do so? Windward or leeward of the buoy … ? Right, leeward of the buoy.

But how do we get there? By bearing away or by heading up … ? Let’s think about it. What happens when we head up while sailing close-hauled … ? We get in irons and get stuck. Or we tack. If we tack we only get leeward the buoy when we bear away afterwards and that takes us away from the buoy. When we want to get back to it we have to move the stern through the wind (jibing), which we have not learn yet. Or we have to do a Quick-turn. That would be tacking twice for which we would need a considerable distance and a lot of time.

So what is the helmsman doing while calling the commands … ? Right, he bears away. He wants to get leeward the buoy as fast as possible to shoot up head in wind. This is definitely the case when he sails close-hauled or beam reach when the buoy falls overboard. If he is sailing broad reach he stays on course, because if he bears away there is the danger of an accidently jibe.

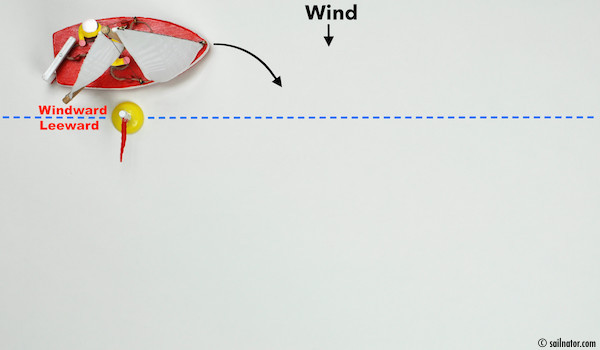

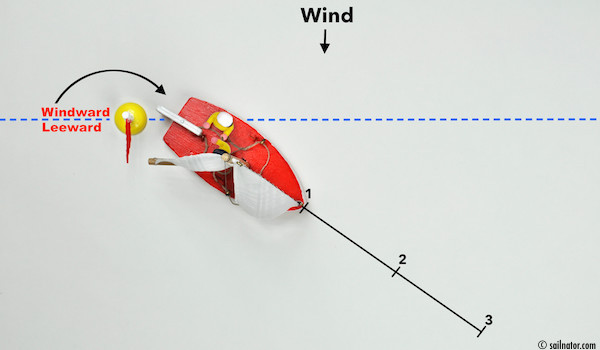

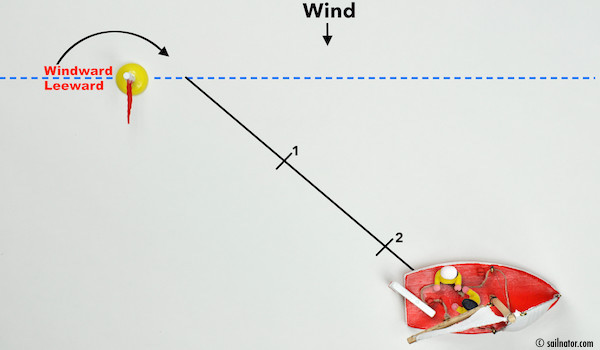

Figure 73: The Helmsman bears away. Commands: “Buoy overboard on starboard! Lookout … (Name of a crew member)! Throw life ring!”

But how do we realise that we have borne away far enough … ? Right. As we have learned before the jib collapses behind the mainsail in its wind shadow. But if this should happen the sails have to be trimmed properly for course broad reach. So the helmsman calls … ? Right: “Ease sheets to broad reach!” (Figure 74) The crew still keeps the swimmer in sight. On a dinghy the crew eases the jib sheet until it luffs. He can hear the noise of the luffing jib and does not have to look at it.

Figure 74: Command: „Ease sheets on broad reach!”

The helmsman in the meanwhile pulls the tiller. He trims the mainsail to course broad reach and is only watching the sails. Induced by stress he might bear away too fast. Maybe the jib is not trimmed properly or he realises too late that it has already collapsed. Maybe a wave made this happen. The accidently jibe occurs. The stern moves through the wind, the boom swings from one side to the other. Hopefully no one has his head in between. Potentially the boat capsizes and everybody is in the water now.

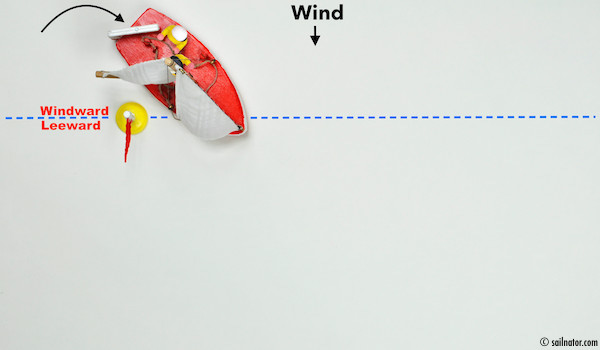

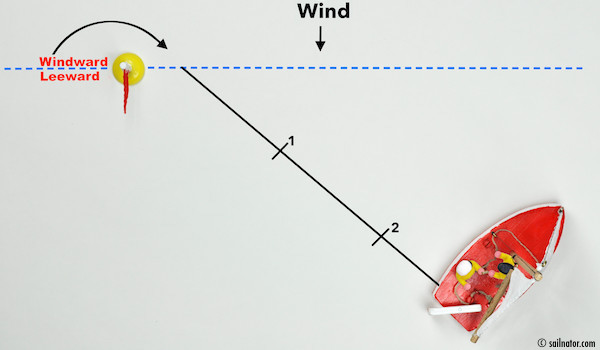

Figure 75: The boat uprights itself from heeling and the jib collapses.

To prevent an accident the helmsman has to look for another sign that shows him that he is already on course beam reach and that the jib will collapse in the next moment. (Figure 75) What could that be … ? By bearing away from beam reach to broad reach we start sailing with the wind in our back and the thrust by lift change to thrust by resistance. Because the wind blows diagonally from behind it does not push the boat to the side and there is no heeling any longer. The boat sails upright now.

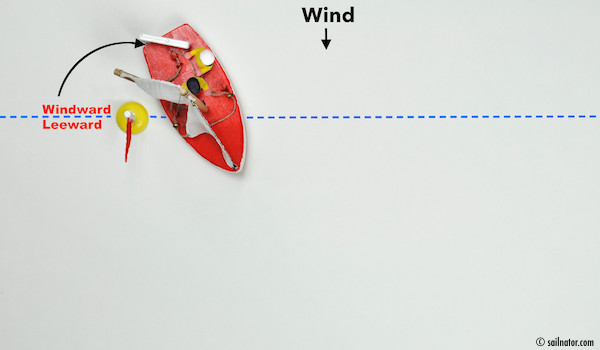

Figure 76: The helmsman heads up immediately till the jib fills and stays on course.

So let’s start from the beginning again. Watch the figures while reading this: We sail on course close-hauled. (Figure 72) Where does the helmsman sit… ? Right. He sits windward. In our case on … ? Right, on port side. The sails are trimmed to which side … ? Right, to starboard. Are they eased or are they hauled … ? Right, they are hauled.

This online sailing course has also been published as ebook and paperback. For more information click here!

This online sailing course has also been published as ebook and paperback. For more information click here!

You can download the Ebook for example at:

iTunes UK & iTunes US | iBooks for iPad and Mac

Amazon.com & Amazon.co.uk | Kindle-Edition

Google Play | for Android

The paperback is available for example at:

Amazon.com | Amazon.co.uk

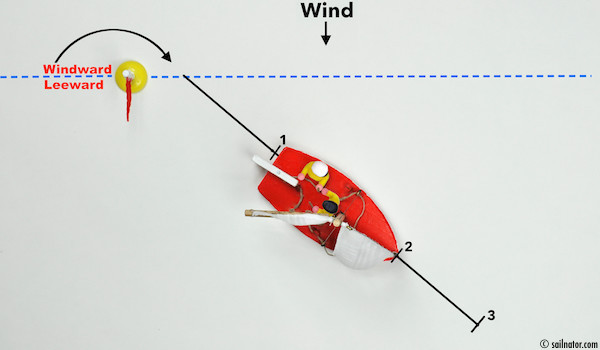

The buoy falls overboard (figure 72), the commands are called (Figure 73) while the sheets are eased and the helmsman pulls the tiller. (Figure 74) He does this till the heeling stops and the boat sails upright. Now he puts the tiller back to the middle. After that he probably keeps on bearing away a little bit, being careful, till the jib collapses. (Figure 75) Then he heads up immediately (Figure 76) till the jib fills again. The crew now sits in the middle of the boat because there is no heeling anymore.

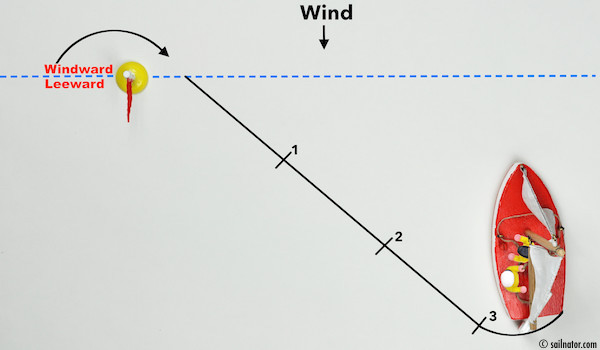

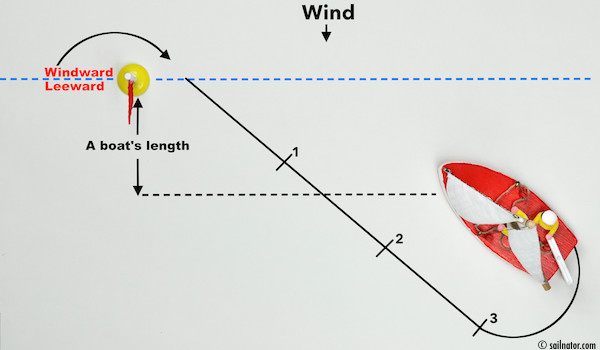

Meanwhile the boat has sailed some distance. But the helmsman does not know how far the boat is away from the buoy. He still watches the sails to keep course and to prevent an accidental jibe. Meanwhile the crew did nothing else than keeping the buoy insight and easing the jib sheet. But now the helmsman calls: “Lookout, count!” (Figure 77) That means that he wants to know the distance counted in boat’s length. But not the distance to the buoy is important to him but how far he is leeward the buoy.

Figure 77: Crossing over the windward-leeward line. Command: “Lookout, count!” The lookout looks and points to the buoy!

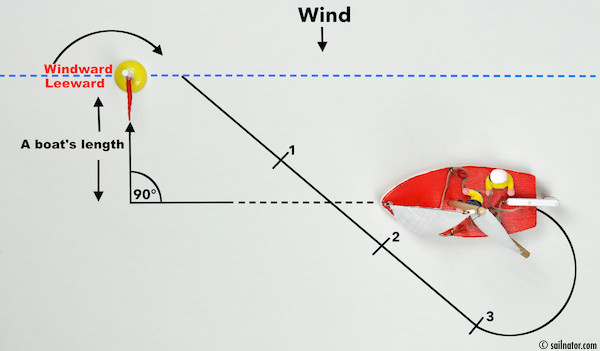

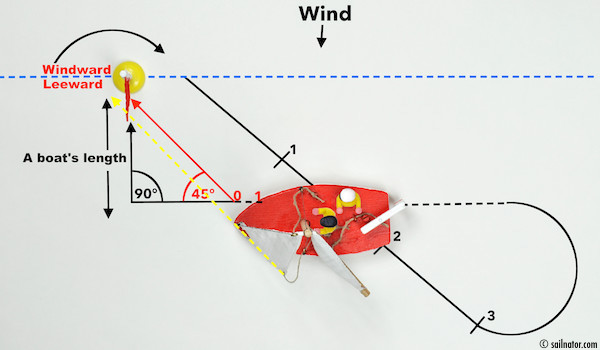

The crew now thinks about where the imaginary line between windward and leeward is located. As an aid he looks for the wave that just hits the buoy. As soon as the distance between the windward-leeward line and the boat is about a boat’s length he starts to count: “1!” (Figure 78) By the second boat’s length he calls: “2!” (The length of a dinghy is about 15 feet, but not about 1000 feet long. That is the length of a super tanker!)

Figure 78: A boat’s length distance to the windward-leeward line.

Figure 79: Two boat’s length distance to the windward-leeward line. Command: “Ready for Quick-turn?” Answer: “Ready!”

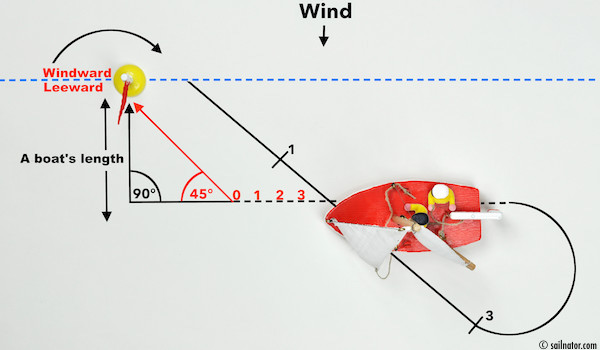

If the helmsman hears “2!” he calls the command for the manoeuvre that he is going to sail now. Which one … ? Right, the Quick-turn. (Figure 79) He has to turn to get back to the buoy. After the Quick-turn we sail on a course about a boat’s length distance parallel to the windward-leeward line. From there we can shoot up head to wind to the buoy.

Figure 80: Three boat’s length distance to the windward-leeward line. Command: “Helm’s alee! Trim sheets!”

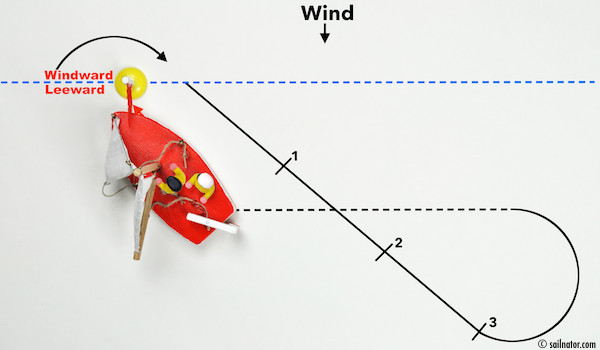

The command is … ? Right: “Ready for Quick-turn!” The response of the crew is: “Ready!”, after that: “3!” as by now the distance to the windward-leeward line is 3 boat’s length. The helmsman calls: “Helm’s alee! Trim sheets!” He starts to head up now and the sails are trimmed without any further command for every new course and for tacking. (Figure 81 & 82)

Figure 81: The Quick-turn.

Figure 82: The bow moves through the wind.

The crew tries to keep the buoy in sight even when tacking. That might be difficult because the boat starts to heel again and he probably has to leave his place from the middle to the windward side of the boat. He still points to the buoy with his arm. Meanwhile the bow moves through the wind and the helmsman has to change to the other side. In this moment he has a short look at the buoy for the first time. He now has to find out where he is. (Figure 83) Is the boat still leeward of the buoy after tacking or did it get back windwards again? Is he too far leeward or is he nearly back at the windward-leeward line?

Figure 83: The helmsman has a quick look towards the buoy and asks himself if he has to sail on close-hauled or bear away to reach it.

He asks himself now: “Do I have to head up or to bear away to find the line in a boat’s length distance parallel to the windward-leeward line?” If he sails up head to wind from too far away he will not reach the buoy. If he shoots up from too close the boat sails past the buoy. However the goal is to stop exactly at the buoy.

Figure 84: Approaching the buoy with a boat’s length distance parallel to the windward-leeward line.

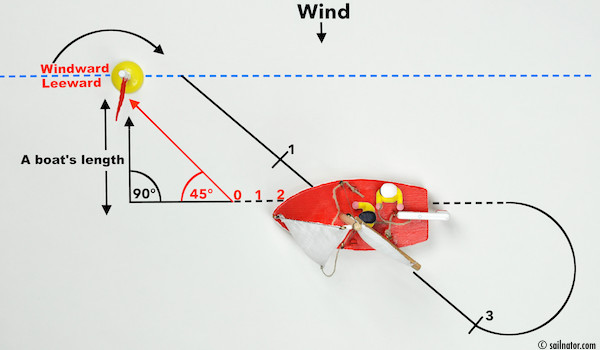

The helmsman levels off to the right course (Figure 84) and calls the command: “Count down!” (Figure 85) This time he does not mean to count boat’s length. He wants a count down like at the start of a space rocket. He does not want to fly to the moon, but to shoot up head to wind. But how does the crew know when the right moment to shoot up is?

Figure 85: The crew releases the jib sheet and counts down.

There is a little trick: Underway to the buoy the crew releases the jib sheet. It will be blown diagonally backwards by the wind. While sailing we still have the wind of motion. Together with the true wind it constitutes the apparent wind. This has the effect I described before. If there was only the true wind the jib would be blown straight downwind.

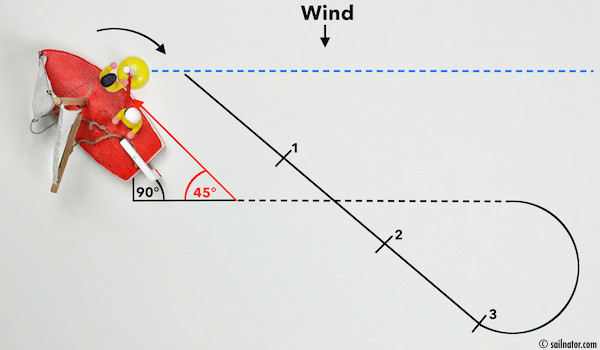

When the jib sheet is released and the jib points diagonally backwards the clew and the tack of the jib line up with the buoy at one point. (The yellow dotted line on figure 87) That is the right moment to shoot up head to wind.

Figure 86: The lookout counts down: „3 … 2 … 1!” Helmsman commands: „Ready to nearly shoot up?”

It works like this: The crew releases the jib. He estimates the time till clew and tack of the jib are in line with the buoy. Then he starts to count down: “ 3 … 2 … 1“ “Ready to nearly shoot up?” (Figure 86) The crew answers: “Ready! 0!” Then the helmsman commands: “Release sheets!” and now does what he announced before: He nearly shoots up head to wind!

Figure 87: Clew and tack of the released jib are in line with the point where the boat is supposed to stop. The crew answers: “Ready! … 0!” The helmsman releases the main sheet.

Why nearly and not directly into the wind? When shooting nearly up head to wind we do not shoot up straight in an angle of 90 degrees of the line in a boat’s length distance to the windward-leeward line. We cut the 90 degrees angle in half and shoot up at a 45 degrees angle. It is actually quite close to sailing close-hauled, just with sails released.

Figure 88: Command: “Ready to pick up the buoy (windward) on starboard! Crew give directions !”

There are advantages and disadvantages to this method. With a dinghy the advantage outweigh the negatives in my opinion. A dinghy is light and capsizes easily. When we shoot up head to wind properly the boom is in the middle when the boat stops. But mostly there are waves and when there is no speed anymore a boat is not in our control anymore. We cannot control in which direction the boat turns. And it will turn.

Let’s say we really have to rescue a swimmer who is starboard of our dinghy and the boat stops head up to wind: The crew wants to grab the person, the boat heels because of the crew moving their weight starboards. The boom moves as well and hits the crew’s head who forgot to be careful in all this hustle and bustle. Or the first wave lifts the boat up and the bow swings uncontrollable to starboard onto the swimmers head. Or the boat turns to port side and we do not reach the person anymore.

When we are caught in irons we have no speed to do anything. We have to sail the manoeuvre again and that takes time. We would also have to do it again if we shot up head to wind from too far away. We will stop shortly in front of the swimmer and not reach him. We can avoid all of this by shooting up nearly head to wind.

The mainsheet has also to be released when shooting up nearly. (The jib sheet was released before.) The boom will be blown leewards by the wind and is out of the way. If we misjudged the distance and stop to early we can haul the sheets again. This is because actually we are sailing course close-hauled when shooting up nearly. Maybe we have to bear away a little bit to gather speed. If we are too fast we try to break by pushing the boom against the wind by hand.

To pick up the buoy without danger of being hit by the luffing boom we have to approach it in a way that the boat is leeward the buoy. (Figure 88) When the boat stops the boom also moves leewards and is out of the way. In our case the buoy should be on which side of the boat … ? Right, starboard. The buoy (or a swimmer) does not easily get caught under the hull when it (or he/she) is windward of the boat.

When everything happens as planned we sail up to the buoy now. The helmsman calls on which side the crew shall pick up the buoy. In our case: “Pick up buoy starboard!” (Figure 88) Shortly before the boat reaches the buoy it is hidden by the bow and the helmsman cannot see it anymore. Because of that the helmsman commands: “Give directions!” From now on it is the job of the crew to show the helmsman how to reach the buoy but not driving over it.

He calls: “Starboard!” when the helmsman hast to steer to starboard and “Port side!” when the helmsman hast to steer to port side. But he does not have to repeat his command like a stuck record. Except if it seems as if the helmsman cannot hear him. To say it once is enough. And the next command is only said if the direction has to be changed.

As I said before there might be acoustic problems. The waves are beating and the sails are luffing. The crew is facing and therefore also talking to the front. Behind him the helmsman does not understand a word. Because of that the crew supports his commands by gestures. He points his arm in the direction the helmsman should steer to. To point to starboard he takes which arm … ? Right, the right one. To point to port side he takes the left arm. (When he sits in front of the helmsman showing him his back) We just stretch our arm out, not brandish it. Some people confuse starboard and port side in all this stress. (But not just then) So when the crew calls port side but points to the right the helmsman should better steer to starboard.

Figure 89: Mainsail and jib are blown leeward by the wind! The buoy can be picked up safely behind the shrouds without any danger. The crew calls: “Buoy is caught!“

Great. Almost everything went well. The buoy lies on starboard next to the boat. The boat stands still and the leeward boom does not disturb us. (Figure 89) The only thing we should take care of now is to grab the buoy when it has passed the shrouds. If possible we should do it that way. If we jump onto the deck in a real emergency and try to pick up a person (what we certainly do when there is no other possibility to get the man) we might have a problem.

In all the stress a boat will never stop properly when shooting up. I will always make a knots speed or so. When catching a light buoy we will have no problem in picking it up. But a human being is quite heavy and sluggish in water. Maybe he is wearing tarpaulin that has soaked full of water by now. When we catch his arm it is as if we try and hold on to a stake.

The weight of the swimmer pulls us back in direction of the stern even when the boat sails at a very low speed. But there are the shrouds in between and we get stuck. Because of the excessive stress we have to let go of him. Maybe the helmsman catches the person by luck. But that costs time, nerves and strength. Most likely the manoeuvre has to be repeated.

When we pick up the buoy behind the shrouds we do not get into these troubles. We sit safe in the cockpit. The danger to be pulled overboard by the weight of the swimmer is reduced. We can lead the person to the stern and pull him back on board. Trying to get him back into the boat at the side, might capsize the boat.

Now after all, the buoy is safely on board. The crew calls: “Buoy is caught!” and the helmsman commands: “Haul sheets to close-hauled!” Now we can go on practicing. For that we beat up windward for a while, because we probably drifted quite far leewards during the manoeuvre. And then we throw the buoy overboard again and practice, practice, practice! We should be able to sail it in our sleeping, like a robot. And we have to get a feeling for the respective boat. So when we sail a new boat we always sail the MOB-manoeuvre first!

Watch my stop motion video about man overboard →

So what should we remember about the man overboard manoeuvre:

The jobs of the helmsman are: bear away – call commands – watch the sails to prevent an accidental jibe (the boat does not heel anymore / the jib collapses / head up again) – Quick turn – sail along a line in a distance of a boat’s length parallel to the windward-leeward line – shoot up nearly head to wind

The jobs of the crew are: Lookout!!!! => Never lose sight of the buoy! – point in the direction of the buoy – release jib sheet till jib luffs – count the boat’s length after crossing the windward-leeward line – locate the buoy after the quick-turn – release jib sheet – countdown – guide the helmsman to the buoy – pick up the buoy behind the shrouds

Now an overview of the commands as I have suggested:

Crew: Buoy overboard starboard/portside!

Helmsman: Buoy overboard starboard/portside! Throw life ring! Lookout … (name)!

Ease sheets for broad reach!

Lookout, count!

Crew: 1.. 2..

Helmsman: Ready for Quick-turn?

Crew: Ready! 3!

Helmsman: Helm’s alee! Trim sheets!

Count down!

Crew: 3 … 2 … 1

Helmsman: Ready to nearly shoot up head to wind?

Crew: Ready! 0!

Helmsman: Release sheets!

Ready to pick up the buoy starboard/port side?

Give directions!

Crew: starboard / port side / straight ahead

Buoy is caught!

Helmsman: Head down to starboard/port side! Haul sheets to close-hauled!

If you want to use this commands you should not use them right from the beginning. It is more important to learn the process first. In my experience the language memory and the motor skills memory do not match at all when learning. When the buoy falls into the water and you first have to think about what to say the only word that comes out of your mouth will be: “Um, well … “ and in the meanwhile you have sailed away three boat’s length. You only have to say 3 words but you will not remember them. My advice: practice till you learned the sequence of action and then start with the commands. Please remind that my commands are only a suggestion to you. It may be that your sailing instructor uses different terms!

In the next chapter I will explain jibing to you. This is how to safely move through the wind with the stern.

← Last chapter | Next chapter →

All chapters: Technical Terms | The theory behind sailing |Close-hauled | Beam reach | Broad reach | Sailing downwind | Tacking | Beating | Quick-turn | Sailing up head to wind | Man overboard | Jibing | Heaving-to | Leaving the dock | Berthing | Rules of the road 1 | Rules of the road 2 | Rules of the road 3 | Reefing | Capsizing